Coming Out When You're A British South Asian

/There’s a pivotal moment in Gurinder Chadha’s 2000 film, Bend it like Beckham, when Tony (Ameet Chana) tells his best friend Jas (Parminder Nagra) that he “really likes Beckham.” When Jas realises that Tony is coming out to her she is astonished. “But you’re Indian!” she says. The joke, albeit a hollow one, is one that is familiar to most British South Asians LGBT people, even now. It is painfully present, even after the sixteen years that have passed since the film, and after the strides made by LGBT people in the general British public.

I don’t have a similar coming out story. When I began to accept my lesbian sexuality, In the early 90s, I was too scared to tell anyone in the British Indian community of which I am a part, that I rejected the heteronormative narratives that were being pushed on me from all angles. From Bollywood films to the wider Indian community, the message of marriage and of family duty was unwavering and omnipresent. In my own family I was told repeatedly that good Indian girls get married, preferably to doctors or lawyers, have children, and live near their parents.

At family events The Aunties would appraise me, as they did most marriageable young adults at the venue, and suggestions would be made for potential marriages. They spoke to me, too, but I was always incredulous and often rude, about their plans. But to actually come out and say the words “I am a lesbian” would have meant certain community rejection.

Parminder Nagra and Ameet Chana in Bend It Like Beckham (2002)

At school, one of very few pupils of colour, I tried hard not to stick out, so disclosing Sapphic tendencies was not an option. Many other friends who are LGBT of colour cite the same experience. It is lonely, living what was in effect a double, or even triple life. As a recent ex-teacher I know this struggle continues, especially for people with South Asian heritage. Young adults still feel that they have to choose not only between the "normal" school experience and possibly being bullied but also between their sexuality and their community. Add to this another factor in deciding whether to stay in the closet or not: the fear of the racism that’s still prevalent in the LGBT community as it is in the wider community.

One particularly upsetting event will always remain with me. In the late 90s a group of mostly Asian men and women were marching past a local gay pub in Walthamstow, in East London. The demonstration was quite small but the banners were colourful, unfurled, and there were rallying shouts. It was a warm Saturday afternoon; some of the regulars stood by open doors and windows, sipping drinks. “Look,” someone says “It’s P*ki Pride”. There was some laughter, and only some demurral.

Put up with racism or homophobia? Some choice! It is sad but unsurprising to me that British South Asians continue to choose their families over the unknown leap into the LGBT community. I wish I could meet them all, tell them that I’ve built my own, diverse LGBT family. That my parents know now and they still love me (my mum in particular has been unbelievably accepting), and that theirs may feel the same way. That my life, with my wonderful wife and wide group of friends, is better and more open than I could ever have hoped for when I was a scared teenager.

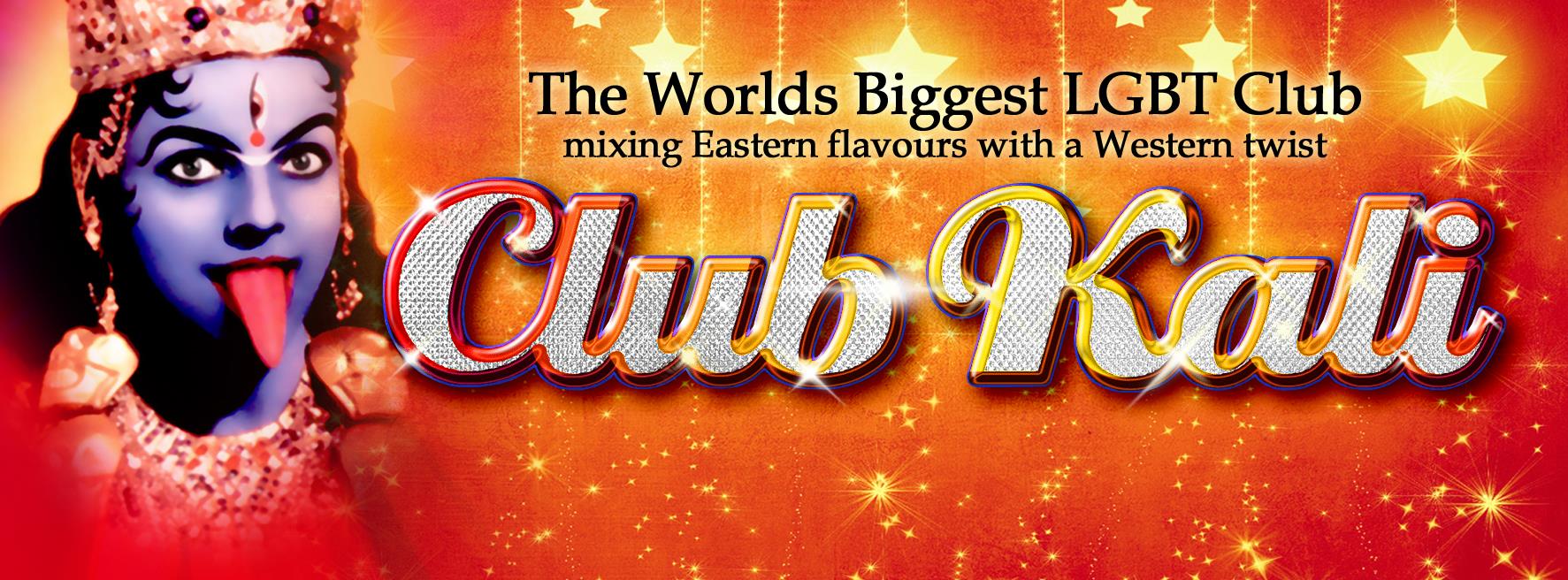

I want to tell closeted South Asians that there are places they can go to, like Club Kali in North London, where they will find out and proud South Asians who can offer support. In the mainstream media, and even in the gay media, South Asians will generally see narratives about white cis men and women. Don’t be fooled. LGBT people of colour are everywhere. When I first went to Club Kali I saw lesbians who looked like me for the first time, with brown skin and black hair, with bangles, and bindis and chunnies and kohl-ringed eyes. There were other South Asian lesbians. I wasn’t alone! I remember crying, tears of joy.

When I first came out as a lesbian, activists had to invent a South Asian science because the larger gay community wasn’t that welcoming. But that has improved. There is an accepted and identifiable LGBT South Asian presence out there now, and there are campaigns to increase the visibility and representations of all LGBT people of colour.

Life as an out British South Asian lesbian is not without its challenges. I still sometimes feel conspicuously gay at South Asian events and brown in LGBT clubs and pubs. The idea that you can’t be a gay Indian is hard to kill off. And some adversaries are less easy to vanquish. The Aunties still come up to me at family weddings, after all these years, and despite the fact many of them know. After all, I’ve caught family members googling me. More than once.