The Will Of Someone Who Wants To Live

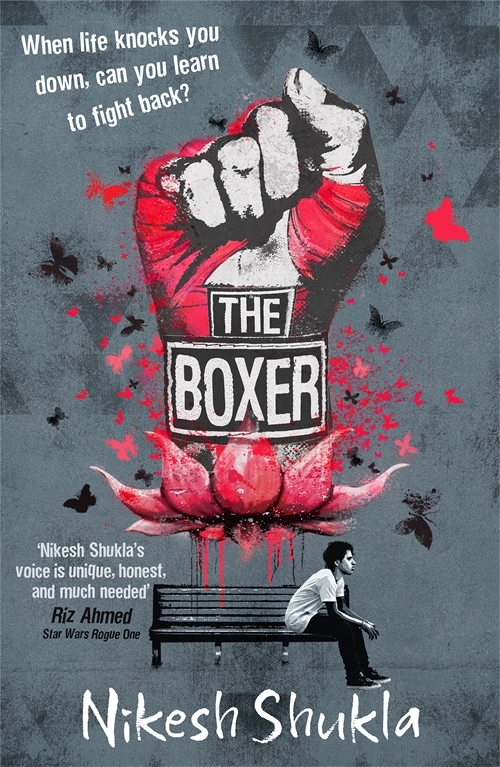

/Nikesh Shukla is an author, responsible for classics The Good Immigrant and The Good Immigrant USA, as well as many others (The One Who Wrote Destiny, Coconut Unlimited and Meatspace are brilliant). In the run up to the release of his latest YA fiction The Boxer, he writes about how he has dealt with racism. The Boxer was born from a personal experience Shukla experienced on a train ride home - a train ride that many of us can relate to.

He’s written for us previously, here and here - both pieces are revealing and poignant, connecting deeply with every reader. He doesn't hold back here either, as he divulges the inspiration behind his latest novel. Buy it here.

When they dismiss Andy Ruiz Jr as a fat little kid, he wins. Because what he possesses is strength. For months now, as I box, as I practise combinations, as I punish heavy bags like I would you, that night, when you sought to make me feel small, I’ve been worrying less and less about my weight, and more about strength.

Exercise to me used to be about a return to status. There’s an old photograph I had on my mantlepiece. In it, I am nineteen years old. It is black and white. I have the leather jacket kaka and kaki brought back from India. I have a cigarette dangling from my mouth. I am standing in the doorway of the BFI on South Bank Centre. Adam and I have framed the shot so that I look like James Dean, in that famous shot, wearing a long coat, his innocent face opened into an O of surprise as a cigarette clings to his bottom lip. But I am no James Dean and my coat is wrong and if I lift my top lip, the cigarette will fall to the floor. And any acting training reduces the faces I pull, every single one, every motivational prompt, to ‘consternation’. It is a posed photo. I am thin, young and resplendent in monochromatic mood lighting.

I will never look like I do in that photo again.

I spent years looking at it, trying my best to imagine myself in that body. There is decline and there is age and there is the heaviness of a lifetime of bad habits, ill-thought out snacks, snacks to pass the time, snacks to fuel, snacks to keep me awake, snacks because it was a Tuesday, snacks that made me happier, just for a second, while I chewed, snacks that took me back to that perfect time, sitting in front of the television with my mum, sharing crisps, fetching us both ice cream, guzzling peanuts, laughing at American sitcoms, safely ensconced in our home.

I eat because I am bored and because I need fuel - more than I eat because I am hungry.

Don’t underestimate this little fat kid, Andy Ruiz tells Anthony Joshua in the run up to their fight. And there is an extent to which people will look at this short fat kid and not understand the power that rises up through his knees, as he swivels his hips and drops his shoulders and throws hands and bang, snaps his fists into the side of Joshua’s face, one two, bang bang, until our man is on the floor, shaking his head unsure of what happened.

I have given up on that photograph of me. Instead, I think about Ruiz and I think about power and strength. I think about the space I occupy. I think about my weight and how it shifts from knee to knee, hip to hip. I think about my hands, clenched and ready to burst forwards, till my knuckles are on top and my fingers pinch into a solid fist. I think about the roll of my shoulders, how they ebb and flow. I think about power and I think about strength. I think about why I’m here and for who.

That photo of nineteen year old me, it feels like someone else now. It’s not that his body is unattainable. It’s that I do not wish to put my body through what it would take to get to it. I’m increasingly less interested in being thin now. I’m much more concerned with being strong.

I feel shame after each snack, a deep humiliation overcoming me. I will lie to my calorie counter app. I will lie to my loved ones. I will lie to myself. I will punish myself with more intense bursts of exercise, go for walks to sate the step counting app and switch to slimline tonic but none of these will make the difference I need in order to look like that nineteen year old version of me.

I don’t know how to stop.

I work the heaviest bag with as much force as I can muster. I want to be able to floor a rhino. I tense my fists and give my shoulders the fullest roll. I dance around this bag, shuffling my feet across and back and forward and towards, springing back as my body blows make the bag drop, careening towards me with twice my body weight.

The lighter bags, I practise speed over force. The machine with 10 pads set up, I practise precision and combinations. The speed bag, I don’t have the coordination for. I don’t want to be fast. I want to punch with force.

I am punching bad thoughts out of my head. I am punching the hunger down deeper into my body.

Strength has an intriguing side effect that I hadn’t prepared for. I walk with my shoulders spread. I don’t hunch. I don’t look at the floor in front of my trainers. I don’t fix my eyes on the furthest point I can to avoid eye contact. I don’t shuffle so quickly, I lose my step. I think about when Henry introduces the big boss, Paulie, and in his voiceover says, he may have moved slowly but that’s because he didn’t have to move for nobody. That’s me. Don’t underestimate me. My fists are clenched as I walk around, making eye contact with everyone I pass.

I don’t know why those men chose to do this to me but I’m slowly accepting my new state.

Taking up boxing was never about losing weight or developing a body that would make me comfortable walking down the street topless, my t-shirt tucked into the back of my belt, like a tail. It was never about beating anyone up. It was certainly not about aggression. I don’t punch those bags with the mind of a killer. I attack them with the will of someone who wants to live.

Andy Ruiz Jr was a joke opponent. A surefire victory for Joshua. A complete miscalculation. Because they looked at his body type and not at his form or his mind. Ruiz let Joshua’s team misjudge him, the hype undersell him and the public dismiss him. And he snapped into focus when the bell rang.

There’s a moment in the aftermath of any racist attack where you think, for the most pregnant of seconds, that it was something you did.

In that moment, you spend a lifetime trying to work out what you should have done differently. Maybe I should have got a different train, maybe I should have worn a different top, maybe I shouldn’t have tweeted about it as a way of dealing with it, maybe my anger is the real problem, maybe it didn’t even happen and I made it all up for attention, maybe it did happen and it should happen and this country is not for me anymore.

I carry that with me at every point. Except when I face those bags, when I run on that treadmill, when I shadow box around the ring, when I watch myself in the mirror, skipping, thundering up and down, my entire body shaking with the rhythmic bounce of my feet. On tiptoes, I squat and I waggle the warrior rope. I can do one pull up currently, two push-ups with claps. My burpees may lack fluidity but I can dip for four reps. When I toss the huge tractor tyre around the basketball court at the back of the gym, doing baseline runs between each flip, I can feel something I never had before. I feel strong.

A friend asks me every time I see him if I’m still training. I nod. He asks what I’m training for. Glibly, I say, the race war. I wear a straight face before breaking into a smile to let him know I’m joking. Except I’m not joking. Well, I am. A little.

I put the photo of nineteen year old me into a photo album. It’s part of the past now. There is a no photo now. There is only space I’m taking up. Space that was mine to begin with.